I love to wake up in the bush to the chorus of a new day.

My mind is clear from a night of rest and the morning calls are carried in the fresh air. It’s like nature is broadcasting in Dolby Digital, and my senses feel almost superhuman. This is my personal safari story.

During walking trails in the Luangwa Valley in Zambia, I love to get up every day just before sunrise and take a short stroll near camp.

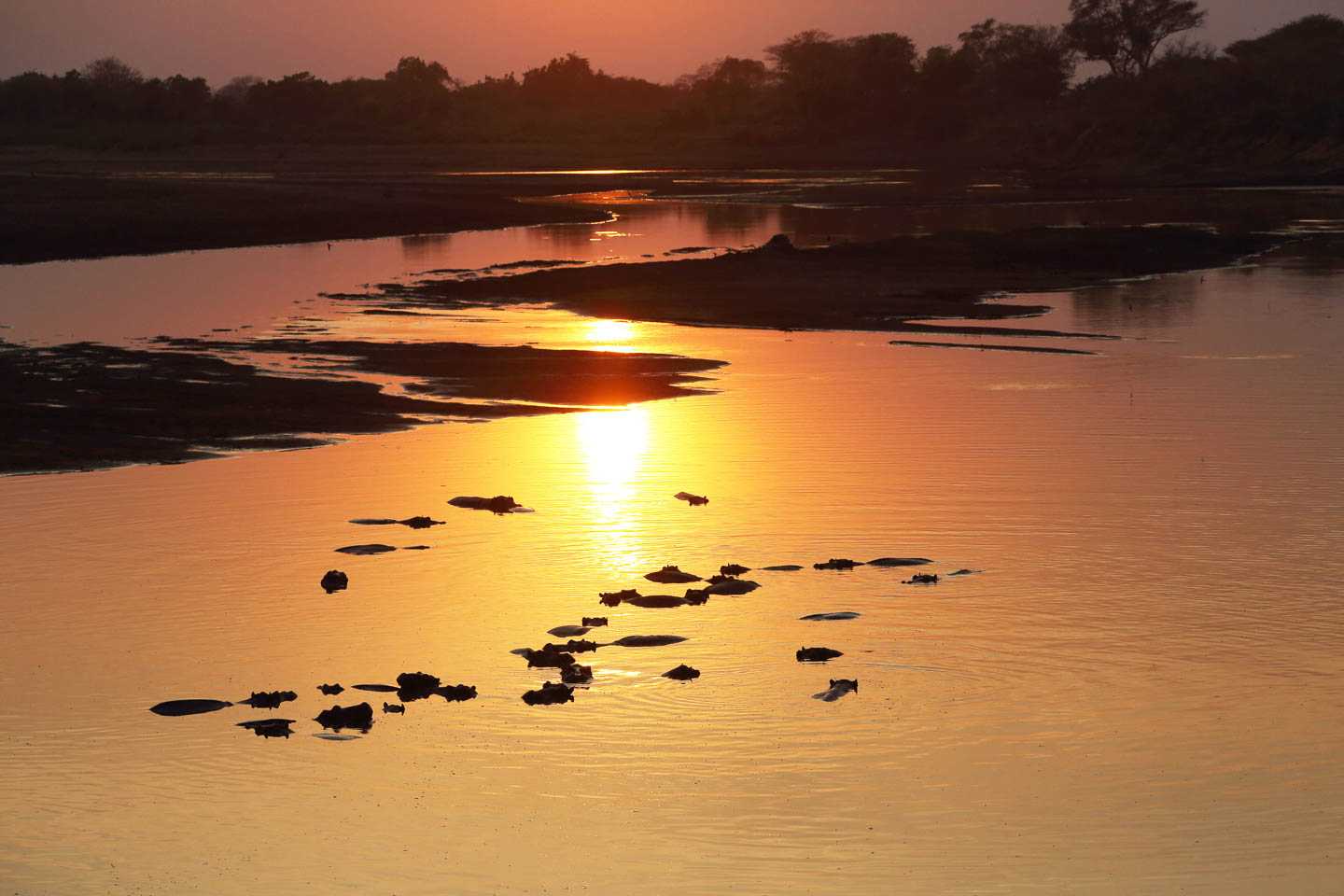

The birds are tuning their loud instruments for the morning show. Hippos sound their baritone grunts from the coffee pools and monkeys chatter in the Jackalberry trees that branch over the winding Luangwa River.

Signs of last night’s party are printed in the sand. A herd of elephants that moved past camp in the dead of darkness; pug marks from the hyenas that wooped outside until 3am; the frightened impalas that skipped by when the lions roared an hour later.

And then: leopard tracks.

The sand still falls from the cusps of the cat’s pug marks, meaning the shy animal passed by only moments before.

There is a reason why senses are sharper and clearer when walking in nature.

Scientific studies have shown that time spent in nature actually makes us more intelligent. We are more creative, better at solving problems, and also have longer attention spans after walking in the wilderness.

Our compatibility with the environment makes sense when you look back into human history. The vast majority of our time on this planet (250 000 years) has been spent living and walking in nature, exposed to the elements, while just a pinprick of that time makes up our pseudo-modern existence.

Genetic studies have shown that the San people of Southern Africa, hunter gatherers who have lived in nature for over 30 000 years, are the oldest human culture on the planet. They are a living, yet fading, example of how human beings coexisted in nature for millennia. Their deep connection to the natural world is best demonstrated in their ability to track and hunt animals for hours, even days, on end. They speak of a spiritual connection to the animals that they are hunting, which is embodied in a great ‘dance’—a pursuit that takes them into the mind of the animal that they are tracking.

In essence, the San are the original nature walkers. And this wilderness is their ancient stomping ground.

The leopard is close, and the skin on the back of my neck begins to tingle.

A predator does not always move silently through the bush. When other creatures become aware of its presence, the thickets begin to reverberate.

The birds, insects, monkeys and other animals all have their way of alarming when there is danger in the area. It’s like a natural police unit made up of volunteers from the whole neighbourhood, and if you are tuned into the frequency, you know what to listen and look for.

Monkeys call their croaking alarm from the top of a jackal berry tree; squirrels shriek from the branches, and a bushbuck barks like dogs down by the river.

My pulse rises. I draw a deep breath, listening. I’m aware of the dangers, but I can feel the pull of the tracks in the sand.

I try to visualise her route, to tune into her mental frequency, to become the leopard. I want to follow her tracks; to trace her wild course along the spine of this ancient river, past 1000-year-old baobab trees, over open grassland plains, through shallow valleys.

I lean into the breeze, and take a step forward.

But there are voices in the opposite direction—the familiar sounds of people at camp. The morning murmurs remind me of safety, of comfort, of belonging.

The kudu bark in the distance, this time further down the river. The leopard is moving fast. A francolin bursts from the bushes and the monkeys chatter away to each other.

I take one last look into the bush, staring deep into the brown to see if I can spot anything, but the alarm calls seem more distant now—the leopard is moving down the bank into into the riverbed.

The bush orchestra plays on.

But the friendly voices at camp draw me home, ending my safari story.

Feeling inspired? Have a look at our favourite Zambia walking safari.